The Absurd Theatre Of War

Tate Britain’s ‘Aftermath’

The most frustrating thing about visiting war cemeteries like the one around the Douaumont Ossuary, as I did more than 10 years ago, is the feeling of utter futility.

This isn’t futility in the sense of ‘lions being led by donkeys’ to slaughter, the old debate about whether or not First-World-War generalship was fit for purpose.

That kind of ‘futility’ is an intellectual process, a rational comparison of battle plans and outcomes, which invariably leads to the kind of cold, reductionist outlook that the statistics impose on you. By this logic, the Battle of Cambrai, for instance, looks like a relatively trifling affair next to other great campaigns; it’s ‘mere’ 90,000 casualties dwarfed by the roughly one million each from the battles of the Somme and Verdun.

But then you visit Verdun, and stand amongst the graves at Douaumont, and the sheer scale of the place almost knocks the wind out of you, row after row of crosses marching away in every direction. (A good 40 percent of Verdun’s total casualties were fatalities.)

That, you figure, must be it – most of the battle’s dead assembled in one place, where you can digest and process properly the awesomeness of their collective sacrifice.

Afterwards, you head home and look it up and you’re surprised, disappointed even. You may well have just visited the largest French First World War cemetery in the world but it contains ‘only’ 16,142 graves. (The ossuary on the peak of the slope above the cemetery contains the remains of multitudes more - at least 130,000 unidentified soldiers.)

‘Wait’, you think, ‘THAT was what 16,000 dead soldiers equated to? Then what the hell would Verdun’s 300,000-plus actual number of dead have looked like?!’ (‘Shrouds of the Somme’ at least gives a sense of the scale of the British death toll sustained on July 1, 1916).

That’s the frustration of not being able to convey to others that you stood amongst, just five percent of the total and even this was overwhelming; because the fact is, processing even such a small fraction required you to be there. A proper appreciation of the place necessitates the juxtaposition of both seeing every grave in the immediate vicinity, of knowing each one of those was once a person, whilst also being simultaneously aware of the vast scale of the place around you.

For me at least, this brief episode serves as a window into better understanding the psychology of the wartime generation. If I had trouble articulating what I’d experienced just visiting a cemetery, they must have felt infinitely more frustrated trying to impart any sense of what they’d seen to non-veterans.

It’s worth remembering too that not only did many of them directly witness the carnage on the battlefields, the whole world around them was permanently altered. The norms of the conservative pre-war era first gave way to conflict on a record-setting scale, then political and economic uncertainty and turmoil followed, eventually leading, as we know, to war on an even vaster scale. It only ended, finally, mercifully, with the arrival of the long-overdue denouement, the era of relative peace, security and mutual toleration we enjoy today.

This explains why many veterans, then and now, turn to art. Without having to fully comprehend or explain the complex events they were still caught up in, war artists could simply reflect what they saw.

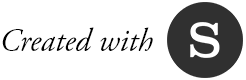

At least, that was what German artist Otto Dix aimed to do with his work, some of which is currently being featured (along with those of many of his contemporaries) at Tate Britain’s ‘Aftermath’ exhibit. The notation beside one of his pictures points out that Dix in fact viewed the artist’s entire role as being that of observer and documentarian.

War: Skull by Otto Dix (1891-1969); 1924; Etching on paper; 257 x 195 mm; The George Economou Collection. © Estate of Otto Dix 2018

War: Skull by Otto Dix (1891-1969); 1924; Etching on paper; 257 x 195 mm; The George Economou Collection. © Estate of Otto Dix 2018

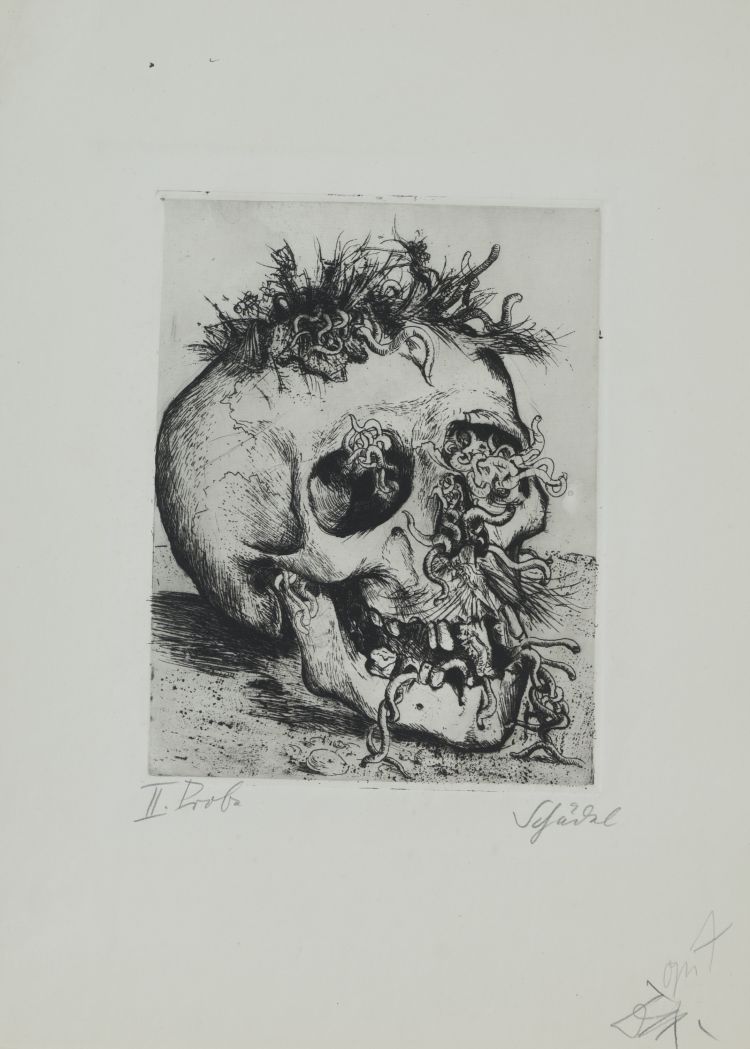

Prostitute and Disabled War Veteran. Two Victims of Capitalism by Otto Dix (1891-1969); 1923; Pen and ink on yellow card-board; 469x 373 mm; LWL-Museum für Kunst and Kultur (Westfälisches Landesmuseum) / SabineAhlbrand-Dornseif. © Estateof Otto Dix 2018.

Prostitute and Disabled War Veteran. Two Victims of Capitalism by Otto Dix (1891-1969); 1923; Pen and ink on yellow card-board; 469x 373 mm; LWL-Museum für Kunst and Kultur (Westfälisches Landesmuseum) / SabineAhlbrand-Dornseif. © Estateof Otto Dix 2018.

Of course, artistic documentation can mean giving as much attention to feelings as to observable facts. Witness George Rouault’s macabre ‘Arise, you dead!’ above, which imagines a battlefield populated with reanimated corpses. (This same motif likewise featured in the climax of the 1919 film ‘J’accuse’, in which a French soldier is chased home from the frontlines by an army of undead former comrades.)

Conversely, British artists CRW Nevinson and Paul Nash didn’t require walking corpses to make their work ghostly – their realistic portrayals of battlefields are haunting enough.

Nevinson’s ironically titled ‘Paths of Glory’ adorns the cover of this article and has been refashioned in the style of an Otto Dix multi-panel painting below. Tate Britain says of the piece that the:

“…depiction of soldiers’ bodies left to rot in a wasteland was banned by the military censor. Nevinson exhibited it in 1918 with a diagonal strip of brown paper inscribed ‘censored’ covering the corpses. The title comes from a line in Thomas Gray’s 1750 poem, ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard‘: ‘the paths of glory lead but to the grave‘. Nevinson worked with a Red Cross ambulance unit in France between November 1914 and January 1915, returning to France as an official war artist in July 1917.”

Nash’s ‘Wire’ is just as powerful, despite the absence of the dead. Rather, the countryside itself is the casualty:

“Mud, shell holes and dead trees vividly convey the destruction of war... Trees had been important symbols in Nash’s pre- war landscapes. In Wire the splintered tree stump encircled by barbed wire suggests a mutilated body. Nash was stationed at Ypres in Belgium between February and May 1917. He returned there as an official war artist in late October 1917, near the end of the Battle of Passchendaele, and was shocked by the destruction it had caused to the landscape.”

Off the battlefield, German artist George Grosz, like Dix, focused on the lives of ex-soldiers in Weimar Germany:

“‘Daum’ is an anagram of Maud, the name Grosz gave to his partner and later wife, Eva Peter. In this satirical take on the traditional marriage portrait, Grosz presented a couple for modern times. The robotic bridegroom (given the artist’s first name) has a mask-like face and crutch extending from one arm. His appearance references The Spirit of Our Time – Mechanical Head 1919, a human head constructed of tools and objects by fellow Dadaist Raoul Hausmann. The bride is a sexualised figure, fondled by a disembodied hand. Grosz had served in the German army and made a number of violently anti-war works attacking the corruption within wartime and post-war capitalist society. He was a member of the Communist Party of Germany from late 1918.”

‘Grey Day’ was even more overtly political:

“Grosz first exhibited this work under the title ‘Council Official for Disabled Veterans’ Welfare’. It was received as an explicit statement against the lack of support for veterans facing difficulties in post-war life. The suited official in the foreground is a caricatured bureaucrat with briefcase, coiffed moustache and pursed lips. He is walking away from a veteran, hunched in profile, whose welfare he is supposed to oversee. His position of power also contrasts with the faceless worker who crosses the modern city square behind.”

In ‘To the Unknown British Soldier in France’, British artist William Orpen was also critical of those in government:

“Orpen was sent to record delegates at the Paris Peace Conference at Versailles in 1919. Disenchanted with the contrast between posturing politicians and the heroism of ordinary soldiers, he reflected, ‘after all the negotiations and discussions... the only tangible result is the ragged unemployed soldier and the Dead.’ In his final painting at Versailles, Orpen imagined the flag-draped coffin of the Unknown Warrior in the Hall of Mirrors where the Peace Conference had taken place. The original version of the painting also included two ghost-like soldiers guarding the tomb.”

What Orpen’s ‘To the Unknown British Soldier in France’ is to the lost soldiers, Nevinson’s ‘Ypres After the First Bombardment’ is to lost places. In it, he depicts the town of Ypres under artillery bombardment in the early stages of the war:

“Ypres in Belgium was a key base for British troops during the war. Strategically significant, it was repeatedly bombed by German forces. The damage to the town became a recurrent motif for artists and photographers documenting the impact of war on the civilian population. Nevinson presents the scene from multiple angles, allowing the viewer to see into the deserted houses from above. This creates the eerie feeling of a town emptied of life.”

Ypres was eventually rebuilt, though not all settlements were - Fleury at Verdun, for instance, was left with white posts in place of buildings, a memorial to a now-dead village.

Not included in Tate Britain’s exhibit are the paintings of German artist Ludwig Meidner. Although his work resembles Nevinson’s rendition of Ypres under fire, its exclusion can be explained very simply: Aftermath is about the war and the years that followed it, whilst Meidner’s paintings predate the conflict.

His reminiscence about his life in pre-war Germany is quoted in the documentary series ‘The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century’:

“It was a time unlike any other, in the brooding metropolis of Berlin. I was very poor, but not unhappy. I had made a home for myself in a cheap studio, with an iron bedstead and a number of boxes that served as tables. Food was a minor matter, but canvas seemed the most valuable thing there was. I was in love with it and I was not ashamed to kiss it with trembling lips before painting those ominous landscapes.”

The ‘ominous landscapes’ represented the mass turmoil he sensed would soon engulf the continent:

“I didn’t paint from life, but what my imagination bid me to paint. I felt like a hound in a wild chase, mile after mile to find his master: a finished oil painting, filled with apocalyptic ruin. I feared those visions.”

The series acknowledges that Meidner’s expressionistic, destruction-filled cityscapes were truly prophetic – art not just as reflection of current events, but also of an artist’s sense of foreboding; art as premonition.

“Daum” Marries herPedantic Automaton “George” in May 1920, John Heartfield is Very Glad of It (Meta-Mech. Constr.After Prof. R. Huasmann) by George Grosz (1893-1959); 1920; Watercolour, pencil,pen, ink and collage on card; 425 x 319 mm; Berlinische Galerie,Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Berlin; ©Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018.

“Daum” Marries herPedantic Automaton “George” in May 1920, John Heartfield is Very Glad of It (Meta-Mech. Constr.After Prof. R. Huasmann) by George Grosz (1893-1959); 1920; Watercolour, pencil,pen, ink and collage on card; 425 x 319 mm; Berlinische Galerie,Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Berlin; ©Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018.

Grey Day by George Grosz (1893-1959); 1921; Oilpaint on canvas; 1150x 800 mm; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Acquired by the FederalState of Berlin. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018.

Grey Day by George Grosz (1893-1959); 1921; Oilpaint on canvas; 1150x 800 mm; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Acquired by the FederalState of Berlin. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018.

To the Unknown British Soldier in France by William Orpen (1878 –1931); 1921-8; Oil paint on canvas; 1542 x 1289 mm; © IWM (Art.IWM ART4438)

To the Unknown British Soldier in France by William Orpen (1878 –1931); 1921-8; Oil paint on canvas; 1542 x 1289 mm; © IWM (Art.IWM ART4438)

Amongst Aftermath’s pieces from the post-war period is ‘Demonstration’ by Curt Quermer, which reflects the rise of class consciousness in the Weimar Republic:

“In this painting Querner shows himself and his brother-in-law, fellow artist Willi Dodel, in a demonstration for workers’ rights. It is a powerful expression of solidarity with the proletariat, and reflects the artist’s belief that art should address working-class viewers. A member of the Communist Party of Germany living in the workers’ quarter in Dresden at the time, Querner was very aware of the dehumanising effects of mass unemployment.”

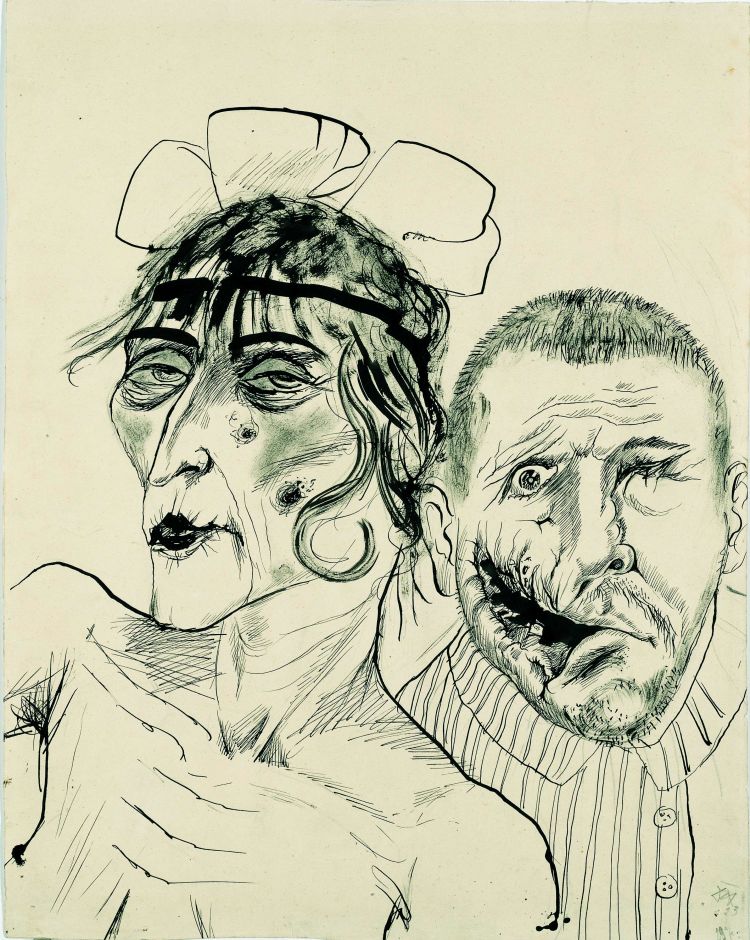

Edward Burra’s ‘The Snack Bar’ contrasts Querner’s work with a depiction of middle-class comfort in the form of a city café:

“The glowing lightbulbs suggest this is a night-time scene. The barman and customer and the smaller figures beyond (including just a pair of legs in high-heeled shoes) suggest the possibilities for pleasurable encounters and consumption available in the city’s leisure spaces at night. Burra was too young to have served in the First World War but by 1930 had spent time in London, Paris and Marseille.”

As well as class issues, any survey of post-war art must surely include something on Jazz. And so Tate Britain’s does, in the form of William Roberts’ ‘The Dance Club (The Jazz Party)’:

“Roberts was a frequent visitor to Soho jazz clubs such as the one depicted here. In the 1920s, transatlantic networks of artists, musicians and authors helped to shape London’s cultural identity. The Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African American art and culture, including jazz, was a particularly strong influence. Roberts had served as a gunner on the Western Front and worked as an official war artist after the war. During the 1920s he regularly painted scenes depicting people enjoying modern forms of leisure, including jazz clubs and the cinema.”

And then there was Dada.

This was an artistic movement that sought to question and upend the existing artistic order, because, as Vic Reeves puts it in the BBC’s ‘Gaga for Dada: The Original Art Rebels’:

“In a world where governments created carnage, and the normal order had become nonsensical, the Dadaists felt the only appropriate artistic response was to be truly and deliberately absurd.”

With a mission that broad, Dada quickly took on multiple and varied forms. One of these was an archetypal form of aleatoric art. Public poetry events were held where printed words were cut up, randomly reassembled and then read out to an audience:

“…the meaningless, pointless, senseless words within the poetry (were) a reaction against the meaningless, senseless, pointless war that was surrounding them; or were they just trying out something new and having fun with it?”

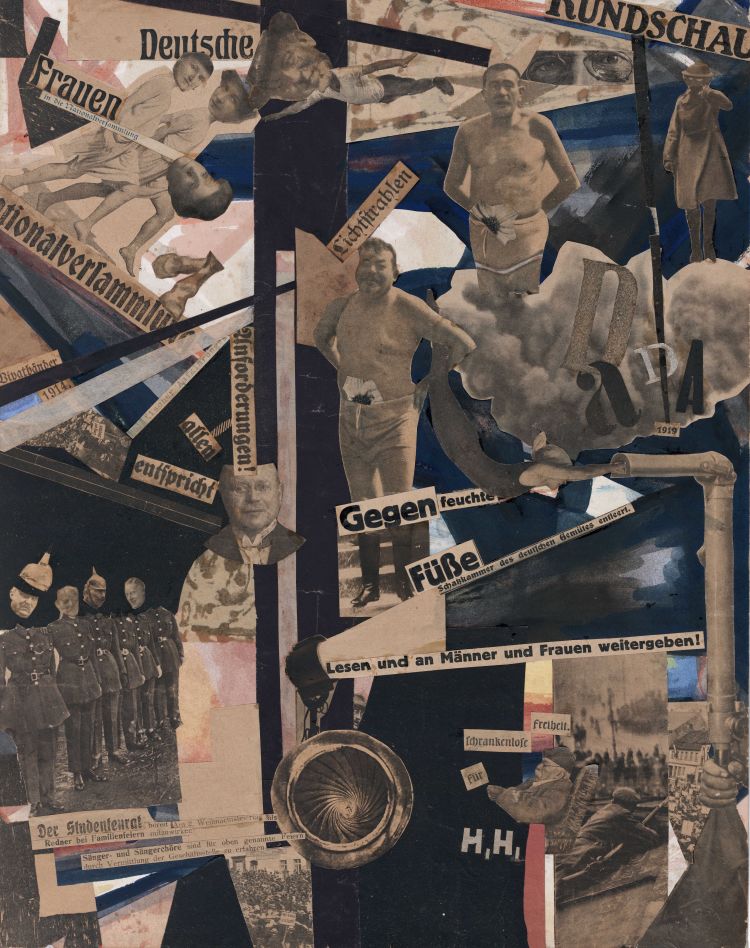

Two examples of the variety to be found within Dada visual art are Self-Portrait’ by Christian Schad and ‘Dada Review’ by Hannah Hoch. The former features a man in a transparent shirt next to his naked lover. Blatantly sexual material is, of course, often thought of as inherently provocative on some level – it must have seemed even more edgy and subversive given the more conservative social mores of the time. Meanwhile, Dada Review consists of a bizarre photomontage lampooning powerful public figures like German president Friedrich Ebert, who is shown wearing a bathing suit.

Eventually, ‘absurd’ turned into more than just an adjective to describe Dada and became a full-blown artistic movement of its own: ‘Absurdism’ became theatrically avant-garde in France and, like Dada, it was informed by the enormity of, in this case, World War 2. Unlike Dada, it poked fun not so much at the existing social order but at the very notion that life itself had any inherent meaning or purpose. How could it, after so much widespread, random death and destruction?

One example of the Theatre of the Absurd is Eugene Ionesco’s ‘The Chairs’ in which a couple, an old man and woman, invite an audience into a room at the top of a high-rise building to hear something important – it’s implied this will be the meaning of life.

Near the end, the couple announce the arrival of ‘the emperor’, who is invisible, and then of the ‘Orator’, who turns out to be deaf and mute. The play climaxes with what must be assumed to be the final revelation of ‘the meaning of life’: a scribbling the Orator makes on a blackboard that reads “Angelfood” and “Nnaa nnm nwnwnw v”, right after the old man and woman have leapt out the window to their deaths.

A more contemporary example of absurdism is the kind of random humour found in ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ (“And now for something completely different: a man with three buttocks”), and Terry Gilliam’s artwork can only be described as Dadaesque.

Likewise, the fingerprints of Pythonesque absurdism are visible in programs like ‘The Family Guy’ and ‘South Park’. Trey Parker and Matt Stone have explicitly said that Python influenced them. One episode of the show, for example, features a mountain creature called Schuzzlebutt that has a piece of celery instead of a right hand and upside-down Dallas actor Patrick Duffy as its left leg. If that isn’t absurdism, I don’t know what is.

Of course, artistic trends and movements can be difficult to definitively trace – one can’t say for sure that Stan, Kyle, Kenny and Cartman, or Peter, Lois, Stewie and Brian are today’s artistic legacy of the First World War, or that they, or something like them, wouldn’t have emerged without Absurdism and its precursor, Dadaism.

Then again, maybe these important artistic counter-movements required the complete shake up of society caused by the First World War and its sequel to ever get going. In that sense, perhaps the true ‘aftermath’ of the Great War really is some of the humour found in today’s popular culture.

The ‘Aftermath’ exhibit will be displayed at Tate Britain until September 23, 2018. Click here to get more information and order tickets.

Demonstration by Curt Querner (1904 –1976); 1930; Oil paint on canvas; 870 x 660 mm; StaatlicheMuseen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Photocredit: bpk/ Jörg P.Anders ©DACS, 2018

Demonstration by Curt Querner (1904 –1976); 1930; Oil paint on canvas; 870 x 660 mm; StaatlicheMuseen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Photocredit: bpk/ Jörg P.Anders ©DACS, 2018

The Snack Bar by Edward Burra (1905-1976); 1930; Oilpaint on canvas; 762 x 559 mm; Tate; © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London

The Snack Bar by Edward Burra (1905-1976); 1930; Oilpaint on canvas; 762 x 559 mm; Tate; © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London

Dada-Rundschau by Hannah Hoch (1889 –1978); 1919; 437 x 345 mm; Berlinische Galerie,Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Berlin; ©DACS, 2018

Dada-Rundschau by Hannah Hoch (1889 –1978); 1919; 437 x 345 mm; Berlinische Galerie,Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Berlin; ©DACS, 2018